Literature review

1.0 Establishing a foundation for the research project

1.1 Methodology for the reviews

In exploring the extensive field of color theory for this project, I have examined a broad collection of historical and contemporary sources; From influential color theorists, scientists and artists to essential publications that have shaped our understanding of color. This review offers insights into how color functions in both design and society.

Color theory is documented extensively, offering numerous sources and viewpoints across cultures and time periods. The sheer volume of information requires an approach beyond simple linear analysis. This literature review is a critical review as it it analyzing and discussing the content. A critical review is essential for evaluating and synthesizing theories, methods, and findings from existing literature, enabling a thorough understanding of the strengths and gaps in the field (1). Additionally, I incorporated elements of a narrative review, which offers a less rigid structure and emphasizes creating a cohesive narrative to contextualize and synthesize research findings. Unlike systematic reviews, narrative reviews allow for a more interpretive and flexible exploration of themes, making them ideal for this project’s aim of understanding the evolution of color theory and its multifaceted applications (2). This also aligns with the principles of action research, which emphasizes iterative cycles of reflection, action, and refinement in addressing practical challenges within a specific context (3).

To address this complexity within the field, I employed a mapping review approach to this literature review which is particularly suited to exploring the breadth of a research field, identifying key themes and uncovering potential gaps in the literature focusing on mapping the existing body of knowledge and are particularly useful for emerging or interdisciplinary topics (2). In the literature indices, further down, you'll find the sources: books, articles, etc. included in this project with comments and notes. these are the result of this mapping review techniques. Later I develop a circle model with categories within the field which is also a result of the mapping review.

These approaches, as outlined by Maria Grant and Andrew Booth (1), provide a comprehensive framework for exploring the multifaceted and interdisciplinary nature of color in design, ensuring both critical depth and methodological rigor. I have not only identified significant contributions and shifts within color theory but also highlighted less unexplored areas, forming a solid basis for the development of new frameworks and methodologies.

The further methodology of the research project itself can be found on this page.

1.1 Paradigm shifts

I have identified several paradigm shifts that reflect the evolution of color research and its applications. The analysis was informed by comparing critical texts like Aaron Fine’s Color Theory: A Critical Introduction (4) with Taschen’s new two-volume mega book; The Book of Color Concepts by Alexandra Loske and Sara Bader (5). Fine analyzes how color theory is not merely a technical or aesthetic subject but also a reflection of social, political, and cultural power structures. He argues that color theory has been shaped by Western, Eurocentric perspectives and calls for a more inclusive approach (4: Chapter 1 +3). The book provides an in-depth exploration of how color has been studied and applied across disciplines. Fine highlights how the understanding of color often balances between scientific measurements (physics, chemistry) and artistic intuition. Fine invites the reader to consider color not merely as a design tool but as a cultural and political force. This perspective makes the book valuable for those aiming to work more strategically and consciously with color. Fine also suggests that understanding a historical period requires examining its approach to color. Conversely, approaches to color and color theory also reveal much about the period itself (4: page 1). Loske and Bader provide a visual compendium of color systems through the centuries. This monumental work documents the extensive and historically significant role that color theory and the understanding of color have played throughout time and history. My comparison of the two sources, along with additional sources from my literature index, reveal how historical perspectives continue to influence contemporary applications in design and color theory.

1.2 Literature Index

The literature review is anchored in two large indices of references, which have been collected and systematically compiled and categorized. These indexes include historical and contemporary publications, ranging from early color treatises to cutting-edge digital tools and trend analyses. Together, they form the backbone of this project’s research foundation. The indices and their corresponding analyses are presented at the bottom of this page. The first index consist of all sources that have been collected and briefly reviewed. The other index is applied literature that is important for this project in some way that have been synthesized-

2.0 Contextual foundation, research orientation and scope

This research project reflects my position as both a practitioner and an academic in the field of visual design. With over 10 years of professional experience as an independent visual designer and five years as a researcher and educator, my work is grounded in practical expertise and informed by theoretical frameworks. My dual role provides a balanced perspective that merges the practical demands of the design industry with the critical inquiry of academic research. The study draws on insights from literature, industry practices, and empirical observations, with the aim of developing practical tools for designers. A key component of this work involves evaluating how multimedia design students approach and experiment with color in their projects.

2.1 Observations from practice

1) Through my years as a visual designer and educator, I have repeatedly observed significant challenges in how professionals and students engage with and articulate color choices. These observations, made systematically through note-taking and journaling, reveal a consistent pattern of 'hesitation', limited vocabulary and a 'lack of confidence' in discussing and justifying color choices. One recurring observation is the evident discomfort and 'ironic distance' that often accompany conversations about color. Designers and students alike seem to struggle with expressing their rationale for color choices, frequently resorting to humor or overly simplistic explanations. I have noted a tendency to rely on brief, surface-level descriptions - such as “red,” “blue,”, “green” - or slightly more nuanced but still rudimentary terms like “dark red” or “grass green.” There is often an awkward pause or even self-deprecating laughter when individuals attempt to elaborate on their color choices, as if delving deeply into color theory or reasoning risks being perceived as frivolous or overly meticulous. This dynamic may stem from a cultural perception of color theory as a “soft science,” closely tied to aesthetic skills, decoration, fashion and interior design. It is - probably - considered as a feminin disciplin and less important attribute, rather than a rigorous design practice.

2) Another challenge I have observed lies in testing and validating color choices. Designers often rely on think-aloud methods during user testing sessions, but these sessions tend to focus on entire interfaces or visual products rather than isolating color for specific feedback. Test participants frequently lack the vocabulary (as well) to articulate their impressions of color, offering responses like “I like it” or “I don’t like it,” which provide little actionable insight for the designer. The absence of structured methods for testing color choices exacerbates this challenge, leaving designers without the tools to substantiate their decisions or improve their work based on user input.

3) Finally, I have noticed significant gaps in understanding how to analyze and contextualize color choices within branding frameworks or localized cultural contexts.Based on my observations, the three key themes: color presentation (the first), color test (the second) and color branding (the third) will form the focus of my literature review and exploratory design process. These themes emerged through the critical engagement and linguistic framing developed during my literature review, rather than being pre-defined categories. It is through the thorough analysis of sources and reflection on their implications that these areas of focus were articulated. Identified through my practice, interviews and field visits, they reflect significant gaps and challenges in current design approaches to color. My contribution to this field is to provide frameworks and insights that deepen understanding in these areas, ultimately transforming how designers approach and utilize color in their work.

Currently, students and professionals often rely on overly simplistic references, such as generalized online color psychology charts or design blogs (A). The chart below illustrates an example of such oversimplified tools, which exist in numerous variations across online platforms. While these resources can inspire initial ideas, they lack the depth and specificity required for robust color analysis and research. As a result, designers risk making assumptions that fail to resonate with their intended audiences or fully account for the intricate cultural and emotional associations tied to color. By addressing these shortcomings, this research aims to foster a more nuanced, informed, and strategic engagement with color in design practices.

Jutt, Hasnat, 2024 (A)

2.2 The contemporary color paradox

On one hand, color appears to have been marginalized in todays digital era, a phenomenon noted by Aaron Fine, who describes how color’s role has been diminished in some aspects of modern design practice (4: page 5 + chapter 8). This aligns with my observations in paragraph 2.1. On the other hand, there is a growing cultural fascination and interest in the history and significance of color. For instance, I recently encountered a reprinted edition of Répertoire de Couleurs by the Société des Chrysantémistes (6) in the gift shop at Arken Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, alongside Abraham Gottlob Werner's Nomenclature of Colours (7), a historic work mapping colors from nature that was famously used by Charles Darwin. Similarly, paint catalogs now feature evocative names like “Masala,” “Cloudy Day,” and “Royal Velvet,” emphasizing the narrative potential of color. There are several aesthetic coffee table books, either about historic color models or modern interpretations of color psychology and how the affect our everyday. Three examples:

- The Anatomy of Colour (8) by Patrick Baty is an in-depth exploration of the history and use of color in interior design and architecture. The book delves into historical color palettes, pigments, and their application, offering a rich visual and historical reference for designers and historians.

- Colour Confidence: A Practical Handbook to Embracing Colour in Your Home (9) by Jessica Sowerby offers practical guidance on selecting and combining colors in interior design.

- The Little Book of Colour: How to Use the Psychology of Colour to Transform Your Life (10) by Karen Haller explores the psychological and emotional impact of color.

This renewed interest in color suggests a latent desire to re-engage with color in a deeper, more meaningful way.

My observations highlight critical gaps in knowledge and practice, particularly in the areas of color presentation (and the language related), color branding and testing color. Paradoxically, while I observe a marginalization of color in a professional discourse - I also see a resurgence of cultural interest in understanding color as just described in former paragraph; Colour is kind of trending. This duality is what I term the Contemporary Color Paradox. In a digital era where color theory and selection are radically transformed - and arguably marginalized - there is an emerging cultural effort to revisit the aesthetic, philosophical, and scientific dimensions of color, as also Aaron Fine support (4: page 5 + chapter 8). This paradox underscores the need for contemporary designers to navigate the tensions between these two tendencies: the practical marginalization of color and its cultural re-emergence as a subject of fascination. By addressing this paradox, we can begin to bridge the gap between our historical understanding of color and the demands of modern design practice.

3.0 Current paradigm: Kaleidoscopic colour abundance

Limited Color Access Paradigm: Defined by natural resources as the primary source of pigments, colors were scarce, expensive, and accessible only to the elite.

Unlimited Color Access Paradigm: Characterized by technological and digital advancements, colors have become democratized, ubiquitous, and a central element of identity and expression. This paradigmatic shift has been particularly intensified over the past 50 years with the advent of personal computers, smartphones, improved screen technologies, and AI-based tools. While industrial and digital revolutions introduced intermediate stages, this study focuses on this large-scale shift, where color has become omnipresent and integral to both design processes and everyday life (4, page 8).

My initial assumptions about how we approach and work with colors in the contemporary paradigm have been significantly nuanced. Initially, I imagined that the seemingly limitless possibilities offered by modern tools and technologies made designing with color almost effortless, even playful. However, my observations of the paradox within my practice—where designers often struggle with articulation and justification in color selection—challenged this notion. These insights have been further refined by sources such as Aaron Fine, who describes the complexities of color in the digital age, emphasizing how technological advancements can simultaneously expand and constrain our engagement with color.

Therefore, it may be appropriate to further characterize the Unlimited Color Access paradigm as "kaleidoscopic," a term which aptly conveys the overwhelming, dizzying, and sometimes confusing experience of navigating an excess of choices and colors. This descriptor encapsulates the duality of the paradigm, where the abundance of options is both an opportunity and a challenge for designers. This color accessibility presents unique challenges for visual designers. As Fine notes, the absence of foundational education in color science leaves designers with limited vocabularies to articulate their choices and disconnected from the historical and emotional significance of colors (4, page 294). This issue aligns with my observations: a lack of confidence and vocabulary in articulating color choices, insufficient methods for testing and validating color decisions, and a limited ability to contextualize color within branding and cultural frameworks. Fine’s critique underscores the need for renewed attention to color research, proposing that the rich history and scientific contributions of color theory be reintroduced into contemporary practices (4, page 317). As this project argues, the current paradigm demands frameworks and methodologies that not only help designers navigate the kaleidoscopic possibilities of color but also reconnect them with its deeper origins, meanings, and impacts. By doing so, designers can move beyond pre-designed interfaces and superficial choices, fostering a more thoughtful, reflective, and innovative approach to color in design.

As a sidenote, this perspective of the overwhelmed and kaleidoscopic designer likely extends beyond color and its selection. Designers today face an immense expansion of technological possibilities across various facets of design. With access to tsunamis of materials, files, tools, and production methods, the challenge becomes to navigate this abundance while making informed choices and maintaining clarity. It is highly probable that the same issues—managing overwhelming options and fostering intentionality—are equally relevant in these contexts.

Based on this chapter and its sources, I have outlined a set of values for the paradigm shift that provide a sense of the many expanded opportunities of our time regarding color, but also the challenges and consequences they may entail:

4.0 Further paradigms

By comparing Aaron Fine’s Color Theory: A Critical Introduction (4) with The Book of Color Concepts by Alexandra Loske and Sara Bader (5) and other sources, I observed several historical paradigmes. Below are the headings, notes and resources from the divergent research phase:

1: The Primordial Palette: The Foundations of Color in Human Culture

Time Period: Ancient Times (Pre-Common Era)

Earliest Uses: Natural pigments, such as ochre and charcoal, employed in cave paintings and rituals.

Symbolism in Ancient Societies: In Egypt and Mesopotamia, colors like blue and gold were used to signify divinity, protection, and power.

Sources:

Primary Source: "Pigments and Paints in Ancient Egypt" - British Museum Research Publications.

Secondary Source: The Colors of History by Clive Gifford - An analysis of color in early civilizations, including Egypt and Mesopotamia.

2: Philosophical Constructs of Color: Light, Divinity, and Beauty

Time Period: Classical Antiquity (c. 500 BCE - 300 CE)

Greek Theories of Light and Color: Philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle viewed color as a manifestation of divine order, emerging from light.

Color in Roman Art: Roman mosaics and paintings reflected social status and beauty through the use of mineral-based pigments.

Sources:

Primary Source: On Colors by Aristotle - A foundational philosophical examination of color.

Secondary Source: Color and Meaning: Art, Science, and Symbolism by John Gage.

3: Sacred Hues: The Theology of Color in Religious Art

Time Period: Middle Ages (5th - 15th Century)

Symbolism in Christian Iconography: Colors gained distinct meanings, such as blue for the Virgin Mary and red for martyrdom.

Illuminated Manuscripts: Luxurious pigments like lapis lazuli were used, linking wealth with access to vibrant colors.

Sources:

Primary Source: The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry - Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Secondary Source: Colour in Art: A Brief History by John Gage.

4: The Renaissance Spectrum: Innovation in Light and Composition

Time Period: Renaissance (14th - 17th Century)

Advances in Light and Color Theory: Figures like Leonardo da Vinci explored the interplay of light and shadow in relation to color.

Development of Oil Paints: Artists achieved vibrant, layered compositions, transforming the artistic palette.

Sources:

Primary Source: Bright Earth: Art and the Invention of Color by Philip Ball - An accessible history of pigments and their influence on Renaissance art.

5: The Scientific Revolution: Rationalizing the Nature of Color

Time Period: Early Modern Period (17th - 18th Century)

Newton’s Prism Experiment (1671): Groundbreaking work revealed color as an inherent property of light, leading to the first scientific color wheel.

Goethe’s Psychological Approach: Theory of Colours (1810) highlighted the emotional and sensory aspects of color, contrasting Newton’s work.

Sources:

Primary Source: Opticks by Isaac Newton.

Secondary Source: Goethe’s Theory of Colours by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

6: Democratizing Color: The Industrial Chromatic Revolution

Time Period: Industrial Revolution (19th Century)

Synthetic Pigments: The invention of synthetic dyes revolutionized accessibility and affordability.

Systematic Color Organization: Albert Munsell’s chromatic systems influenced design, manufacturing, and education.

Sources:

Primary Source: A Color Notation by Albert Munsell.

Secondary Source: Chromatopia: An Illustrated History of Color by David Coles.

7: The Bauhaus Paradigm: Functional and Psychological Color

Time Period: Modernism (20th Century)

Color in Function and Design: The Bauhaus movement integrated color into architecture and design, focusing on its functional and spatial properties.

Advances in Color Psychology: Studies linked color to emotional and psychological responses, shaping fields such as branding and marketing.

Sources:

Primary Source: Interaction of Color by Josef Albers.

8: The Digital Kaleidoscope: Standardization Across Mediums

Time Period: Digital Age (Late 20th - Early 21st Century)

RGB and CMYK: Digital systems standardized color reproduction for screens and print.

Pantone’s Universal Standards: Industry-wide adoption of Pantone transformed visual communication and branding.

Sources:

Primary Source: Pantone: The Twentieth Century in Color by Leatrice Eiseman and Keith Recker.

Secondary Source: Color and Meaning: Practice and Theory in Renaissance Painting by Marcia B. Hall.

9: Sustainable and Intelligent Color: A New Era

Time Period: Present and Future (21st Century)

AI in Color Design: Algorithms generate customizable palettes, offering designers unprecedented precision.

Eco-Friendly Practices: Growing emphasis on non-toxic pigments and sustainable color production.

Sources:

Primary Source: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Business by Steven Finlay.

Secondary Source: The Secret Lives of Color by Kassia St. Clair.

5.0 Perspectival reflection:

Why do we observe chromophobia?

In this context, an intriguing reflection emerges. A hypothesis developed during this literature review is that the rising popularity of “muted,” desaturated color palettes - minimalist schemes, black-and-white or sepia filters, and interior design trends favoring earth tones or “neutrals” (as exemplified by the Wabi-Sabi aesthetic) - might represent a counter-reaction to the overwhelming, kaleidoscopic, and omnipresent explosion of color we have witnessed in recent decades.

Paradoxically, the growing interest in historical methods of pigment production reflects a nostalgic return to the artisanal, as seen in the work of artists like Margrethe Odgaard or David Coles’ recent book, which revisits the roots of natural pigment creation and their historical significance (13). This revival underscores how tradition and craft are influencing modern preferences amidst this kaleidoscopic context.

5.1 Chromophobia: The aversion to vibrancy

In exploring this trend, the concept of chromophobia becomes particularly relevant. Coined by David Batchelor in his seminal work Chromophobia (14), the term refers to a deep-seated cultural aversion to bright, vibrant colors, often perceived as excessive, vulgar, poor or unrefined (11, page 6). Historically, chromophobia has been tied to the Western preference for the “pure” and the “neutral,” often associated with rationality, order, and minimalism, in contrast to the vivid or saturated hues linked to emotion, the exotic, the queer or the primitive. This aversion is evident in the contemporary turn toward muted palettes, which not only reflect a minimalist aesthetic but might also signal a psychological response to the overstimulation of color in our current digital and media-saturated environment.

"In this light, the growing embrace of desaturated and natural tones could be interpreted as an attempt to reclaim balance and authenticity in an era where vibrant, digital colors dominate both screens and branding interfaces. But it could also be a historically embedded legacy. As Kassia St. Clair writes in her book The Secret Lives of Color: "A certain distaste for color runs through Western culture" (12, page 29). The Protestant Reformation of the 16th century, during which vivid colors were stripped from churches in Northern Europe (ibid), exemplifies a cultural understanding of color as a negative phenomenon. During this period, color was often viewed with suspicion and associated with idolatry, excess, and the Catholic Church’s ornate rituals. Similarly, in the Middle Ages, it was taboo to mix colors, as this was seen as a disruption of the natural order (12, page 17).

Before Newton’s discoveries, it was widely believed that colors were caused by impurities in glass, and pigments were often considered dirty and unethical substances (11, page 9). Newton’s work, therefore, not only revolutionized the scientific understanding of color but also represented a groundbreaking and culturally radical shift in the perception of color itself (11, page 9).

The cultural prehistoric aversion to vivid hues persisted into the Renaissance, where art and theory made a stark distinction between disegno (drawing) and colore (color). Disegno was celebrated as intellectual and pure, while colore was dismissed as vulgar and effeminate - a perception that contributed to the marginalization of color in intellectual discourse (12, page 30). Many classical writers also shared a dismissive attitude toward color, seeing it as a mere distraction from the true glories of art: line and form. To them, color was self-indulgent and, at times, even sinful (12, page 17). This historical bias against color extended to the way it was conceptualized. In the Middle Ages and Antiquity, colors were understood as part of a spectrum ranging from white to black, with all other colors falling in between. Newton’s groundbreaking work on the prismatic nature of light in the 17th century thus not only revolutionized the scientific understanding of color but also challenged deeply ingrained moral and cultural views that had long associated color with impurity, falsehood, and sin (12, page 30). Moreover, Newton’s development of the color wheel set in motion three centuries of color publications and models, including circles, manuals, and guides for naturalists, artists, designers, decorators, and educators (11, page 10).

“Men in a state of nature,” Goethe wrote in his Theory of Colours (1810), “uncivilized nations and children, have a great fondness for colours in their utmost brightness.” (17). He further noted that “uneducated people” and southern Europeans, especially women, gravitated toward vibrant colors, wearing vivid attire such as colorful bodices and ribbons. Contrastingly, he observed that people of refinement in northern Europe displayed an aversion to such bright hues, preferring the simplicity of white and black both in dress and in their surroundings. This preference reflects a cultural inclination toward minimalism and restraint, emphasizing rationality and order over the exuberance and emotionality often linked to vivid colors. The dichotomy Goethe highlighted remains relevant to contemporary discussions of color. His observations underscore an enduring cultural ambivalence in Western traditions, where color has historically been perceived as both alluring and excessive. This duality not only shaped aesthetic preferences but also reflected broader societal values, including distinctions between social classes and regional identities (16). In this context, chromophobia - the cultural suspicion or avoidance of vibrant colors - emerges as a recurring theme in Western attitudes, connecting historical perspectives to present-day trends in muted and desaturated palettes.

5.2 Aesthetic and Cultural Implications

The interplay between these trends raises critical questions for visual designers: Is the preference for muted and natural tones a rejection of modern color excess, or does it represent a deeper cultural shift toward simplicity and sustainability? Moreover, how does this tension influence design practices, particularly when navigating the dual imperatives of individuality and trend conformity?

6.0 From cataloging colors to curating colors

Another theme I have examined and emphasized in this literature review is the contemporary approach to color use within visual design, fashion, interior design etc. In today’s expansive color landscape, systematic curation and standardization of colors remain essential practices. Pantone (B), Peclers Paris (C), Lidewij Edelkoort (D) and danish Pej Gruppen (E) engage in extensive cultural analysis to forecast trends, providing companies with insights into selecting colors that resonate with the current zeitgeist. In parallel, color management systems such as Pantone and the NCS (Natural Color System) (F) enable businesses to maintain color accuracy across production and branding, ensuring consistency in their visual identities. Additionally, tools like Adobe Color (G) and Coloro (H) offer advanced digital solutions for color precision, application and management, supporting designers in creating cohesive and impactful brand experiences.

In some way we can say that this is reflecting earlier efforts by figures such as Abraham Werner in 1814 (7) and Michel Chevreul in 1839 (15) because they catalog and structure colors (I). But the new and modern tools and methods just mentioned are enhanced by advanced technology and screens. So we see the same approach in a new mediated culture. We find color management systems that ensure accurate calibration across digital and physical media as an example. I will explain the 'mirroring' of these two activities across times as the next topic.

6.1 Selected historical color studies and models

Historically, early color theorists, artist, scientist and designers focused on cataloging and defining colors found in nature (12, page 26). One of the first was A. Boogert who in Klaer Lightende Spiegel der Verfkonst documented and illustrated an extensive range of color mixtures and their applications, creating a comprehensive manual that explored the practice of color blending and the nuances of pigment use:

Scan from Book on color theory, A. Boogert, 1692 (J)

Werner, as another example, mapped hues inspired by the observed nature, closely related to Charles Darwins work and methods. He was a mineralogisk and geologist that helped us define different hues and gave us a language for color. He thereby provided a catalogue for artist and scientists (7, Introduction) that he called a Nomenclature. With this by hand artist and scientist were able to describe their work with more accuracy:

Scan from Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours, Patrick Syme, 1821 (K)

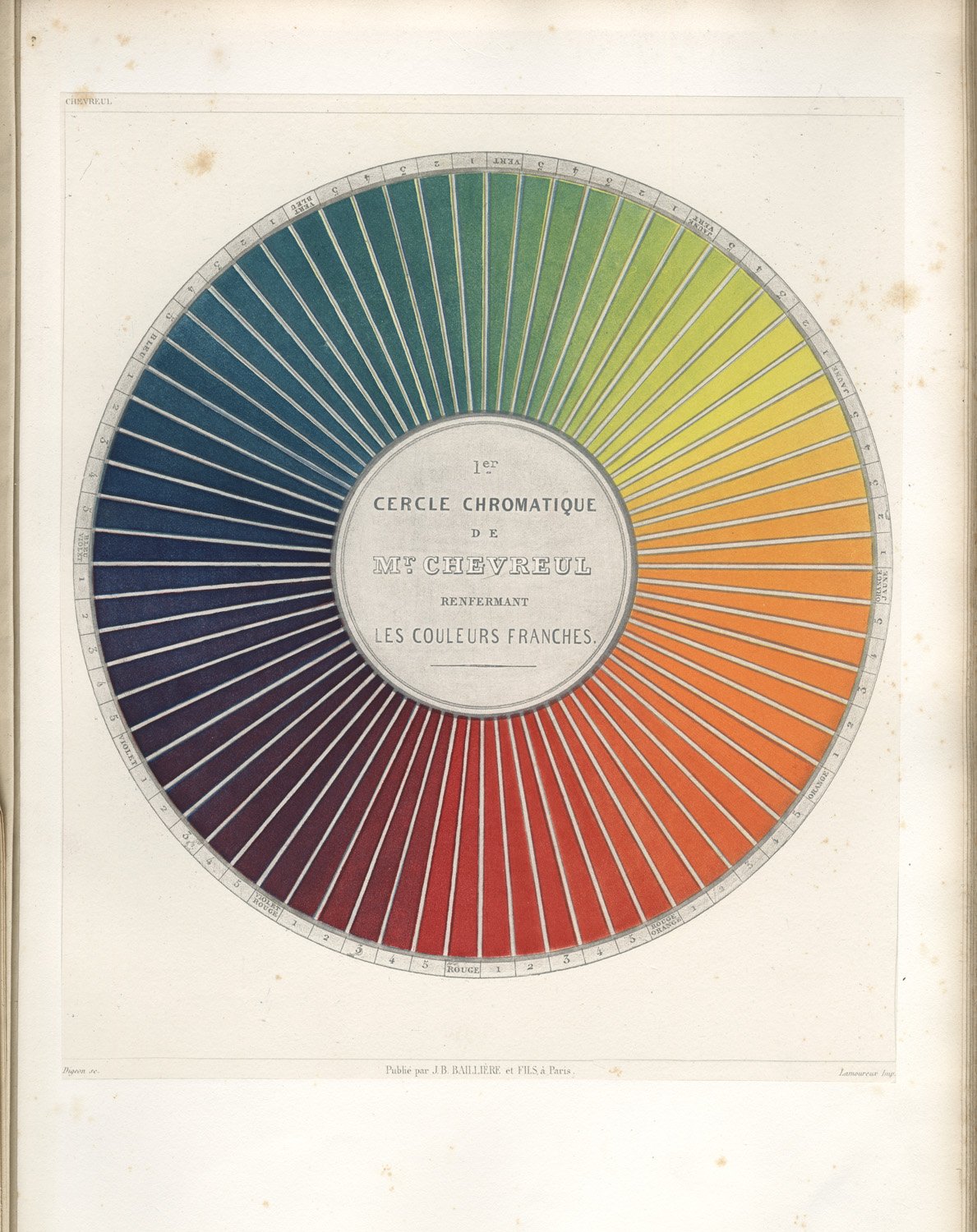

Another important chemist, Michel Chevreul, studied color relationships to deepen the understanding, but furthermore experimented with the production of colors and developed the impressive and groundbreaking Cercle Chromatique with 72 'printed' colors. He invented new colors with other professionals in the foundation of Société des Chrysantémistes. This movement and their color production was important for artist, painters, designers, architects, tailors and craftsmen as they gave new possibilities of using colors in the mid-nineteenth century (11, page 8):

Scan from Micehl Chevreuls Des Couleurs Et De Leurs Applications Aux Arts Industriels a l’Aide Des Cercles Chromatiques, 1864 (L)

Both Werner and Chevreul participated in the work of establish a language for complex color hues observed in the nature, so humans was not limited to call them: red, yellow, green, blue etc. Today, however, as the possibilities for color use have expanded dramatically, the practice has evolved towards curation rather than exhaustive cataloging. Curated palettes and trend guides help designers and industries navigate this expansive field. Thus, the curated palettes serve not only as organizational tools but also as frameworks that provide cohesion and direction, shaping choices and guiding aesthetic consistency in a time of unprecedented color accessibility (11+I). So yes, we can certainly observe a common method and activity when we compare old color science like Werner and Chevreul with more contemprorary processes in working with colors.

6.2 Modern studies and tools

In addition to 'foundational color theories', this study incorporates recent advancements and resources in color practice. Contemporary literature, such as online articles and recent publications, introduces innovative perspectives on the color wheel, often presenting it in 12-color variations. A few examples could be: Color Now by Lin Shijian, which is a practical book that maps color use in different industries and showcases remarkable examples of color use in visual products (17). Or Palette Perfect by Lauren Wager, which introduces concise color theory concepts but provides extensive aesthetic examples of color use and related palettes for designers to draw inspiration from (18). These sources frequently discuss methods for drawing inspiration from various inputs, such as using tools to extract colors from photographs. As I read them these books and sources are more focused on inspiration and ready-mades (fixed color palettes ready to use) and I see these resources as essential in today’s design landscape, as they introduce digital solutions that support designers in creating effective color harmonies (e.g., matching colors in complementary or analogous schemes). I made a comprehensive list of these digital tools and literature on this page (LINK). Building on these contemporary methods, I developed a graphic toolkit (LINK) that features updated color wheels and further demonstrates how these principles are applied practically.

6.3 Paradigm, paradox & language

These tools and this design culture exemplify a practice inherent to the Unlimited Color Access Paradigm as previously introduced. Within this paradigm, the democratization of digital tools and resources has redefined how designers approach color. While these advancements offer unprecedented opportunities, they also highlight the challenges of navigating an overwhelming array of options.

One of the central insights of this project lies in the paradox that many designers encounter today (as previously introduced): While color selection may initially seem straightforward, the complexities emerge when attempting to articulate and justify these choices. I observe that designers frequently find themselves struggling with the abstract qualities of color, leading to simplified explanations, uncertainty, or hesitation. This challenge likely stems from the inherent connection between color and emotional response, as well as the difficulty of translating sensory experiences into language. In other words: I observe that we have a poor language when it comes to colors.

6.4 Colors & Emotion

Colors are intrinsically tied to human emotions, operating on a level that is deeply biological and often unconscious. Frank Mahnke explored the psychological and physiological impact of colors on the human environment in Color, Environment, and Human Response (1996), highlighting their ability to evoke immediate emotional responses. For example, warm colors such as red and yellow can stimulate arousal and energy, while cool colors like blue and green often evoke calmness and relaxation. These emotional reactions transcend individual subjectivity, relating instead to universal human experiences rooted in the limbic system, which governs emotional processing (21).

Robert Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions (2001) further underscores the connection between colors and emotions, categorizing basic human emotions and their intensities. Plutchik argues that emotions operate as adaptive mechanisms, deeply ingrained in our biology. Colors, as sensory stimuli, align closely with these basic emotional states, making them powerful tools for communication and expression in visual design (22). This alignment differentiates emotions, which are instinctual and universal, from feelings, which are more conscious and subjective.

Anne Mette Hartelius introduces the concept of human basic emotions in her book Visual Kommunikation i et Følelsesperspektiv (20). Drawing from Paul Ekman and Stuart Willcox, Hartelius connects these emotions to visual design elements through a "wheel of feelings" (20, page 31). This wheel demonstrates how visual forms evoke and align with specific emotional states. Hartelius’s credo, form follows feelings, suggests a guiding principle for designing visual elements to resonate emotionally. The same principle could apply to colors, extending the alignment of design elements with human emotional responses.

Paul Ekman’s research further elaborates that emotions are challenging to articulate due to their subjective complexity (ibid.), a concept that significantly impacts color design. This observation sets the stage for the next section, exploring the challenges of describing and communicating colors and their emotional impact, especially as subjective layers and nuances come into play.

6.5 Color & language

Color and language are (as well) deeply intertwined. We often lack the ability to convey a color's exact hue to another person and some languages do not differentiate between blue and green (11, page 6). Anthropological research in the 20th century examined whether language shapes perception, asking: Can we recognize a color if we do not have a word for it? Certain studies support this hypothesis, suggesting that language significantly influences how we perceive and categorize colors (ibid). However, other research demonstrates that humans can categorize colors long before acquiring language (11, page 7).

This duality suggests that while our perception of color is sophisticated and advanced, language simultaneously enables and constrains our ability to explore, select, and communicate colors effectively. Designers often struggle not only in their creative processes but also in conveying their choices and intentions to others - that is my observations.

Yet, language should not be the sole focus of this process. Aaron Fine highlights in his work the limitations of linguistic dominance in scientific and rhetorical contexts, noting that linguistic structures like semiotics prioritize: word before image, logic before emotion and language before experience (4, page 300). He critiques the overemphasis on logic and verbal reasoning, suggesting that this hierarchy marginalizes intuitive and non-verbal understandings, particularly with color. Colors are not only seen but felt—they evoke intuition and visceral reactions beyond words. Therefore, this project and its practical tools intentionally allocate space for the intuitive approach to working with colors. I believe that fostering this intuition can enhance understanding and, ultimately, support the development of more precise and effective language (although it may sound ambiguous, paradoxical). While building a robust vocabulary for colors is essential, designers must also cultivate their ability to connect with colors on an intuitive level. This dual approach can enable designers to communicate colors more effectively, both as a sensory experience and as a conceptual message. This interplay between linguistic and non-linguistic understanding paves the way for deeper insights, as explored in the next section on tacit knowledge.

6.6 Tacit knowledge

Tacit knowledge refers to the implicit, non-verbal understanding that underlies much of human expertise and creativity. In The Tacit Dimension (1966), Michael Polanyi defines tacit knowledge as the type of understanding that “we can know but cannot tell” (23). This concept is particularly relevant to design processes, where much of a designer’s decision-making is informed by intuition and experience rather than explicit reasoning. This is described in Anne Mette Hartelius' Visual Kommunikation i et Følelsesperspektiv, as visual literacy; the ability to communicate meaning through visual elements. She frames this as "the designer's tacit knowledge" noting the difficulty of articulating why a particular visual approach may be most effective (20, page 13). This insight applies equally to color, as it is a visual attribute with both communicative and intuitive dimensions.

Aaron Fine introduces a compelling perspective with Frank Jackson’s concept of 'qualia' from The Knowledge Argument from 2009. Qualia represent knowledge that can only be acquired through experience (4, page 301) an idea particularly relevant to colors, which are deeply tied to both sensory perception and emotional resonance. Fine argues that not all experiences can be verbalized or fully captured through scientific discourse, a limitation that applies to our understanding of color (ibid). Colors are both linguistic and experiential phenomena, and I believe that we can gain better knowledge and a better design process if we require a dual approach to the color understanding: through verbal articulation and sensory experience.

The interplay between tacit knowledge and explicit articulation suggests two key strategies for designers: 1) Developing a language for colors to effectively communicate with clients and collaborators, and 2) Honing their intuitive engagement with colors, recognizing and valuing the non-verbal processes that inform their choices. As a designer, you can benefit from embracing and trusting your intuitive senses, engaging fully with your sensory experiences, and later articulating them with confidence and reflection.

6.7 A Missing Link

As part of the explanation of this observed paradox, the concept of the "Brand Gap" is relevant—a term introduced by Marty Neumeier (19). The term has been further elaborated upon by Annette Hartelius, who argues that a vital link is missing between design choices and the vocabulary needed to communicate them effectively (20). In design, bridging this gap requires a disciplined approach to articulating emotional and sensory responses to visual perception: shapes, forms, colors, etc. This gap in communication is not only a linguistic issue but also a cognitive one, as designers often perceive colors intuitively and emotionally rather than analytically (20, page 23).

When it comes to language itself, we have a more developed sense of analyzing words and meanings through rhetorical knowledge and experience. In contrast, the vocabulary for visual perception remains potentially underdeveloped, leaving designers with limited tools to articulate their creative intentions effectively (4, page 293). This gap is particularly pronounced in the context of color, which functions as both a visual and emotional attribute. Design and colors are deeply intertwined with language and emotions - our language shapes how we process and discuss color. Therefore, cultivating a specialized language linked to visual perception, particularly our perception of color, is an essential step in addressing this gap. But 'bridging the gap' related to color, language and emotion is not merely a theoretical exercise; it directly supports the central themes discussed in this review, including the relationship between emotions, language, color and tacit knowledge.

Bridging, or addressing the missing link, has been frequently discussed in this review as a discipline aimed at fostering a deeper awareness of colors and color choices within the design process, potentially developing a more refined language for discussing and presenting color selections. While I believe it is sometimes possible to cultivate such a language, at other times it may be more valuable to preserve these aspects as intuitive, qualia-related disciplines. As Immanuel Kant suggests in his discussions on the sublime, certain experiences—particularly those of profound aesthetic or emotional resonance—resist immediate articulation and instead evoke a sense of awe and complexity that transcends language (24). Kant’s theory suggests that some aspects of design and aesthetics resist immediate linguistic articulation because they operate on an intuitive and sensory level. For Kant, aesthetic judgment does not rely on strict rules or logic but on subjective experience, aligning with the idea of "intuitive, non-linguistic" work in design.

The design process can be understood as an interplay between intuitive and analytical processes in color perception and communication. Addressing the bridge/gap/link enables designers to articulate their creative choices more effectively while also leaving room for intuitive, non-linguistic approaches. This reserved space allows for more complex, emotional, and sensory work methods, which I consider essential for the designer's practice.

6.8 Color Fitness

And how can we then address and practice this interplay or 'bridge building' i relation to color? I will introduce the term Color Fitness, a concept reflecting the idea that designers, like athletes, must continually “exercise” their sensory awareness and descriptive language skills to become proficient in color use and communication. This practice involves developing not only a refined visual sensitivity but also an expansive vocabulary to bridge the gap between perception and articulation. By engaging in Color Fitness, we can systematically improve our ability to describe and communicate colors.

At its core, Color Fitness emphasizes the importance of practice - regularly engaging with and verbalizing visual elements to enhance both comprehension and expression. As Hartelius suggests in her work on visual communication, creating specialized vocabularies or "dictionaries" can facilitate the articulation of complex visual forms and layouts (20, page 13). Similarly, a structured vocabulary for color could help bridge the gap between perception and communication, enabling designers to convey nuanced ideas with greater precision. This aligns closely with the goal of enhancing visual literacy, where language becomes a tool to translate tacit, intuitive knowledge into actionable insights (ibid).

Building on the concept of both an analytical approach and tacit knowledge, Color Fitness thereby addresses a critical aspect of color mastery through two opposing abilities;

Cultivating Intuition: Designers must nurture their ability to connect with colors on an instinctive, non-verbal level. This involves recognizing and valuing the tacit processes that inform their choices, such as the immediate emotional impact of a color or its resonance within a specific context.

Developing Language: Designers must simultaneously work to establish a precise vocabulary for articulating their intuitive insights. By translating tacit knowledge into clear, communicable language, they can better convey their design intentions and the rationale behind their color choices to collaborators and clients.

Interestingly, some online resources (M, N, O + P) start to incorporate gaming among their online color tools. Youtube provides an endless stream of color videos for children with the purpose of learning colors and their names (which is another interesting subject), but for adults I see a few examples on trying to refine and further develop this skill. At the mentioned platforms users need to mix colors to match a given hue, saturation or shade, fostering an intuitive and systematic approach to understanding and manipulating colors. Such tools highlight the potential for integrating Color Fitness into everyday design practices. It is the purpose of this project to develop frameworks and methods to practice Color Fitness more structured and detailed and the literature review is the foundation for this development. This is the topic of the next section.

7.0 Outputs of this literature review

As I collected and studied various sources, I was able to narrow my research focus through a hermeneutic process, allowing for a progressively refined understanding of the field (25). I conducted this literature review to establish a solid foundation for my research project. The literature review itself is a scientific contribution. But this project aims to provide further articles, practical tools and frameworks directly implementable for students and designers in their design processes. It is my assessment that there is a particular lack of practical books offering applicable scientific insights. I see a lot of new color books focusing on giving inspiration on color choice in the early design proces. But I want to apply knowledge and tools about the later design phases as well.

Developing Solutions

So this research introduces practical frameworks aimed at addressing critical challenges in contemporary design practice, specifically within the context of Color Fitness. The solutions proposed here align with three central objectives:

Establishing a stronger vocabulary for visual design: Designers today require a precise and expansive language to articulate their color choices and communicate their design intentions effectively. This framework emphasizes the development of a shared vocabulary, enabling clearer expression and deeper discussions about color decisions within design workflows.

Encouraging intuitive and personal approaches: Beyond linguistic precision, designers should cultivate confidence in their intuitive and personal connections to color. This framework integrates methods that highlight the importance of individual sensory experiences and emotional responses, fostering a more self-assured approach to selecting and working with colors.

Reconnecting with the materiality of color: The rise of digital interfaces has distanced designers from the tangible aspects of color—its historical roots, the evolution of color models, the complexities of pigment production, and humanity’s relationship with color throughout time. By addressing this gap, the framework aims to reconnect designers with the rich material and cultural histories of color, offering a more holistic perspective that enhances both practice and understanding.

Together, these objectives provide a comprehensive approach to empowering designers, bridging gaps in language, intuition, and material awareness. The frameworks serve as tools for navigating the kaleidoscopic abundance of contemporary color options while fostering both analytical and sensory engagement with color in design.

7.1 The Circle Model

Creating this literature review I spent a lot of time collecting and structuring literature. The next step was to analyze and synthesize the material in a typology that serves as both an exploratory tool and a 'compass' to limit the scope of this project. Based on my index of literature, I observe a range of categories within published works.The typology got the name The Circle Model as it identifies specific areas where my work and experience can build upon and extend current theories in a meaningful, contemporary context. You can find The Circle Model if you visit this page. With The Circle Model at hand I had a tool to place and define the developed methods and frameworks even better and it gives a great opportunity relate them to different perspectives.

7.2 Frameworks & Methods

Here follows a list of the articles, frameworks and methods related to this project:

Teaching material - Coming up

VERT - Testing Color - Coming up

Branding Through Color - Coming up

Articulating Color - Coming up

7.3 Indices

Finally, you'll find the two literature indices presenting the essential sources engaged in this research project. The first table serves as a comprehensive index of relevant sources, each examined to build a broad understanding of color theory’s evolution and the various perspectives that have shaped the field. This index offers an overview of the historical and contemporary contributions that have informed the framework and methodology of this project. The second table emphasizes key sources that have deeply influenced my analysis and the specific knowledge contributions this project offers. I did study this literature further in the detail than in the first index. It has enriched my understanding of color as both a technical and aesthetic phenomenon within contemporary design. These sources have not only served as points of reference but have also guided the development of research questions and methodologies for investigating color's role in today’s visual and digital design practices.

The two indices can be found further down this page. You can click at the column categories to sort the index by year or writher.

Sources

Grant, M. J., Booth, A., A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies, 2009, Health Information and Libraries Journal.

Greenhalgh, Trisha, et al., Storylines of Research in Diffusion of Innovation: A Meta-Narrative Approach to Systematic Review, 2005, Elsevier.

Reason, Peter, Bradbury, Hilary (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice, 2008, SAGE Publications.

Fine, Aaron, Color Theory: A Critical Introduction, 2022, Bloomsbury.

Loske, Alexandra, Bader, Sara, The Book of Color Concepts: Volumes 1 and 2, 2024, Taschen.

Société des Chrysantémistes, Répertoire de Couleurs: Pour Aider à la Détermination des Couleurs des Fleurs, des Feuillages et des Fruits. Nouvelle Édition du Répertoire Publié en 1905. 1385 Nuances, Réparties en 365 Planches S'Adressant, 2021, Chêne.

Syme, Patrick, Werners Nomenclature of Colours, With Additions, 1821, Second Edition, Natural History Museum.

Baty, Patrick, The Anatomy of Colour, 2017, Thames & Hudson Ltd.

Sowerby, Joa, Colour Confidence: A Practical Handbook to Embracing Colour in Your Home, 2023, Quadrille Publishing Ltd.

Haller, Karen, The Little Book of Colour: How to Use the Psychology of Colour to Transform Your Life, 2019, Penguin Books Ltd.

Travis, Tim (ed.), The V&A Book of Colour in Design, 2021, Thames & Hudson.

St. Clair, Kassia, The Secret Lives of Colour, 2016, John Murray.

Coles, David, Chromatopia: An Illustrated History of Colour, 2022, Thames & Hudson Australia.

Batchelor, David, Chromophobia, 2000, Reaktion Books.

Chevreul, Michel Eugène, Cercle Chromatique, 1839; Gamme Chromatique, 1864, Librairie Renouard.

Taussig, Michael, What Color Is the Sacred?, 2009, University of Chicago Press.

Shijian, Lin, Color Now: Color Combinations for Commercial Design, 2018, Counter-Print.

Wager, Lauren, Palette Perfect: Color Combinations Inspired by Fashion, Art and Style, 2017, Promopress.

Neumeier, Marty, The Brand Gap: How to Bridge the Distance Between Business Strategy and Design, 2003, New Riders Press.

Hartelius, Anne Mette, Visuel Kommunikation i et Følelsesperspektiv, 2013, Samfundslitteratur.

Mahnke, Frank H., Color, Environment, and Human Response, 1996, Wiley.

Plutchik, Robert, The Nature of Emotions, 2001, American Scientist.

Polanyi, Michael, The Tacit Dimension, 2009, University of Chicago Press.

Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Judgment, 2005, Dover Publications.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg, Truth and Method, 1975, Sheed & Ward.

Links, Online Sources

a) Jutt, Hasnat, Color Psychology: How Different Colors Affect Our Emotions and Behavior, 2024, Medium, Read here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

b) Pantone Official Website, Visit Pantone, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

c) Peclers Paris: Trend Forecasting, Visit Peclers Paris, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

d) Edelkoort Studio, Visit Edelkoort Studio, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

e) PEJ Gruppen Official Website, Visit PEJ Gruppen, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

f) NCS Colour Official Website, Visit NCS Colour, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

g) Adobe Color, Visit Adobe Color, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

h) Coloro: Color System Website, Visit Coloro, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

i) St. Clair, Kassia, Before Pantone, There Was Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours, 2018, Architectural Digest, Read here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

j) Traité des Couleurs Servant à la Peinture à l’Eau, Bibliothèque Numérique, Read here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

k) Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours (1814), Public Domain Review, Read here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

l) Chevreul, M.E., Des Couleurs Et De Leurs Applications Aux Arts Industriels a l’Aide Des Cercles Chromatiques, Paris: J.B. Ballière, 1864, Special Collections, Read here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

m) Color - A Color Matching Game, Play here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

n) TryColors Game: Guess the Mix, Play here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

o) HSL Color Game, Play here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

p) Adobe Color: Color Wheel Game, Play here, Last accessed: 10.12.2024.

Med denne version er links klikbare og kan anvendes direkte i tekstfeltet på din hjemmeside.